[ad_1]

By Will Banyan (Copyright © 09 May 2021)

Depending on whose esteemed works one chooses to read, the Trilateral Commission was either created by the New World Order conspirators as a natural extension of their network of control, or it emerged through the sheer will of David Rockefeller, after his proposals to admit Japan to the Bilderberg Group were rebuffed by his transatlantic colleagues. As an example of the former claims, one need look no further than the final book of the late Jim Marrs, The Illuminati: The Secret Society that Hijacked the World (2017). Marrs claimed the decision to create the Trilateral Commission was largely because of the need to create an alternative organization to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) because it was seen as an “instrument of control by the ‘liberal eastern establishment’” (The Illuminati, p.81). To remedy this, in 1973, plutocrat David Rockefeller and national security academic Zbigniew Brzezinski founded the Trilateral Commission. According to Marrs:

Plans for a commission of trilateral nations were first presented by Brzezinski during a meeting of the ultra-secret Bilderberg group in April 1972 in the small town of Knokke, Belgium. With the blessing of the Bilderbergers and the CFR, the Trilateral Commission began organizing on July 23-24, 1972, at the 3,500 acre Rockefeller estate at Pocantico Hills, a subdivision of Tarrytown, New York (The Illuminati, p.82; emphasis added).

Although Marrs cites no source for this raft of claims, the specific allegation of a Bilderberg “blessing” is echoed in numerous other accounts of the Trilateral Commission’s origins. One of the earliest accounts, cited by None Dare Call It Conspiracy (1972) author Gary Allen in his final book, Say “No” to the New World Order (1987), comes from an article in New York magazine (Dec. 13, 1976) by Aaron Latham:

David Rockefeller went to a meeting of the Bilderberg Group…The Chase Manhattan bank Chairman trotted out his [Trilateral] idea once more for old times sake. The Bilderberg members loved it. Soon thereafter the Trilateral Commission was conceived…(quoted in Say “No” to the New World Order, p.35).

Journalist Robert Eringer presented a similar, more detailed account in his book The Global Manipulators (1981), noting that Rockefeller was apparently “delighted” with Brzezinski’s idea of a trilateral brains trust:

[Rockefeller] tossed the idea around at several Chase Manhattan board meetings and saw to it that Brzezinski was invited to the next Bilderberg Conference. There in April 1972 in the small Belgian town of Knokke, Rockefeller proposed the formation of a Trilateral Commission. Bilderberg participants responded enthusiastically and urged him to press forward with the plan (Global Manipulators, p.56; emphasis added).

Other accounts include Holly Sklar’s edited volume, Trilateralism: The Trilateral Commission and Elite Planning for World Management (1980), for a long time the only substantive academic text about the group. In her chapter giving a chronology of the origins of the Trilateral Commission, Sklar notes that in spring 1972, after Rockefeller had been giving speeches before Chase Manhattan Financial Forums, promoting his idea to establish an “International Commission for Peace and Prosperity”:

[T]he most enthusiastic and most crucial response came…when Rockefeller and Brzezinski presented the idea of trilateral grouping at the annual Bilderberg meeting. Michael Blumenthal, then head of the Bendix Corporation, strongly backed the idea (Trilateralism, p.78; emphasis added)).

Sklar’s account was most likely drawn from an interview with Trilateral Commission Coordinator George S. Franklin by The Freeman Digest (February-March 1979); this report is cited in Sklar’s bibliography. According to Franklin’s account, in 1972:

[David Rockefeller] went to a Bilderberger meeting. Mike Blumenthal was there (now Treasury Secretary), and he said, “You know, I’m very disturbed. . . Cooperation between these three areas — Japan, the United States and Western Europe — is really falling apart, and I foresee all sorts of disaster for the world if this continues. Isn’t there anything to be done about it?” David then thought, “I’ll present the idea once more,” which he did, and he aroused great enthusiasm. The next eight speakers said that this was a marvelous idea; by all means, somebody get it launched [emphasis added]

John B. Judis, in an article in The Wilson Quarterly (Autumn 1991), also suggested Rockefeller’s idea met with approval when he proposed it at Bilderberg:

In the spring of 1972, Brzezinski, Rockefeller, and [C. Fred] Bergsten attended the annual meeting of the Bilderberg Society, held at the Hotel de Bilderberg in Oosterbeek, The Netherlands… According to one participant at the meeting, Rockefeller proposed a tripartite or trilateral organization, and then Brzezinski, acting as if he were hearing the idea for the first time, enthusiastically seconded his suggestion. That July, 17 men, including Brzezinski, Bergsten, Owen, and McGeorge Bundy, met at Rockefeller’s Pocantico Hills estate in the New York suburbs to plan what came to be called the Trilateral Commission (p.48).

A somewhat vaguer account was provided by academic Stephen Gill in his book, American Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission (1991). He noted that the Trilateral Commission had been “launched from within the Bilderberg meetings by David Rockefeller” (p.137) and that: “After David Rockefeller’s 1972 Bilderberg speech, the Commission was constructed” (p.140). But Gill mysteriously provides no actual detail of Rockefeller’s Bilderberg speech.

It is from the late David Rockefeller that we find a somewhat different version of events. Addressing the Trilateral Commission on the occasion of its 25th anniversary, as part of a program of speeches and toasts for their event, held at New York Historical Society on December 1, 1998, Rockefeller explained how he and:

Zbig Brzezinski…went to a Bilderberg Conference in Knokke, Belgium. I thought that the best thing to do, rather than start another organization, would be to persuade the members of Bilderberg to include Japan. I proposed this at the meeting, but was shot down in flames by Dennis Healey, then Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and a very articulate person.

So, my tail between my legs, I left. Zbig and I flew back to the United States and talked about our options. We decided that if Bilderberg didn’t understand the importance of this idea, we’d have to start a new organization ourselves (The Trilateral Commission at 25: Between Past…And Future, Speeches and Toasts, December 1, 1998, pp.1-2; emphasis added).

In his autobiography, Memoirs (2002), Rockefeller gave yet another version of his quest to establish “an organization including representatives from North America, Europe, and Japan”, noting how in 1972:

Zbigniew Brzezinski, then teaching at Columbia University, was a Bilderberg guest that year, and we spoke about my idea on the flight to Belgium for the meeting. I had been urging the Steering Committee to invite Japanese participants for several years, and at our session in April, I was again politely but firmly told no. Zbig considered this rebuff further proof that my idea was well founded and urged me to pursue it (Memoirs, p.416; emphasis added).

Save for the words of Franklin (even though Franklin was not at the 1972 Bilderberg meeting) and Rockefeller, until recently there were few avenues for confirming either of these accounts about the Bilderberg’s role in the formation of the Trilateral Commission. But with the trove of Bilderberg documents on the Public Intelligence website, and recent academic research undertaken into the origins of the Trilateral Commission, it is now possible to examine this claim with greater precision.

Referring to the minutes of the Bilderberg Meeting in question, held over April 21-23, 1972 in Knokke Belgium, we find David Rockefeller’s intervention, during a discussion on the “crumbling community of purpose”:

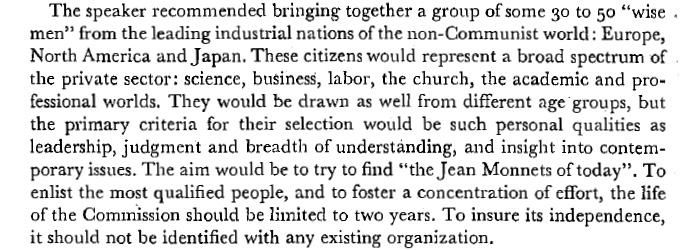

In the introduction to his working paper, the American author had asked, “Who is going to define the road ahead … the common direction in which we must move?” A suggestion in this regard was offered by a fellow American participant, who summarized a proposal he had recently made for the establishment of an “International Commission on Peace and Prosperity”. This idea had grown out of a conviction that national governments – and even international organizations, such as the UN – were so preoccupied with the day-to-day business of managing the complex problems of society that they had little time to think about the future, to try to anticipate the issues of a decade or two hence, and to initiate some thinking about them now (Bilderberg Meetings, Knokke Conference, 21-23 April 1972, pp.55-56; emphasis added).

The “fellow American participant” was indeed Rockefeller, who had already been promoting his “International Commission for Peace and Prosperity” before captive audiences. The plutocrat then took the opportunity to elaborate on his proposal:

Rockefeller envisaged the Commission producing a report that might deal with issues such as “environmental control vs. economic growth; individual freedom vs. egalitarianism; problems of urban life (housing, crime, drug addiction, financing urban education); and so on.” Ultimately the Commissions’ report would be “given to governments and to the public in a manner designed to produce the maximum impact” (ibid p.56). More importantly was how this idea was received. The Bilderberg minutes seem to leave little doubt:

The only discordant note, at least according to the minutes, came from another American speaker (p.57), who warned that the Commission’s work could be still be ignored:

Nevertheless, these minutes, to the extent they can be relied on, seem to highlight a discrepancy between Rockefeller’s version, which seems to fixate on rejection of his proposals to admit the Japanese into Bilderberg, and the other accounts, which stress that Bilderberg had supported his broader scheme to create a “Commission” representing Europe, North America and Japan. Rockefeller claims that his proposal to admit Japan had been “shot down in flames by Denis Healey” are also difficult to verify, with Healey not listed in the meeting minutes as a participant (see p.6), in fact he appears to have been in London for the duration of the meeting.[*] And the meeting minutes also do not record any dissenting opinions from any British attendees.

The obvious answer – one highlighted in Dino Knudsen’s recent deeply researched study The Trilateral Commission and Global Governance: Informal elite diplomacy, 1972-1982 (2016) – is quite simply that Rockefeller was conflating the two proposals. Knudsen suggests that the Bilderberg Steering Committee had again rejected Rockefeller’s push to admit the Japanese to Bilderberg, but at the same time meeting participants had supported his proposal to create an entirely separate organisation bringing the three regions together. Rockefeller, possibly for reasons of ego, chose to embellish his account, to present the Trilateral Commission as his bold answer to Bilderberg’s refusal to admit Japan rather than concede that Bilderberg had in fact given his “Commission” its blessing (ibid, p.39).

The bottom line, though, is that at the very least, Jim Marr’s contention that Bilderberg gave its “blessing” to Rockefeller’s Trilateral Commission is essentially correct. It does not mean that Bilderberg actually created the Trilateral Commission, but rather it points to the simple fact that a number of Bilderberg meeting participants back in April 1972 supported David Rockefeller’s proposal to establish a “Commission” of “30 to 50 ‘wise men’ from…Europe, North America and Japan.” The Steering Committee, although repeatedly refusing Rockefeller’s requests to invite Japanese participants to Bilderberg, implicitly supported his Commission, by ensuring the generally positive discussion around his proposal was recorded in the meeting report for posterity. The rest, to abuse an overused cliché, is history, with Rockefeller and Brzezinski bringing the Trilateral Commission into being, though it remains a matter of some contention if it has truly achieved any of the grand geopolitical goals imagined by its coterie of well-connected founders nearly half a century ago.

As for Bilderberg, it did not host a Japanese participant until 2009 when Nubuo Tanaka, as Executive Director of the International Energy Agency attended, though he was categorized as an “International” participant rather than Japanese. Chinese representatives, in a remarkable contrast, have been repeatedly invited to Bilderberg in the past decade, with Chinese senior diplomats and academics attending in 2011, 2012, 2014, and 2017. In this case, the Steering Committee is either bowing to geopolitical realities or the Chinese have more effective champions within Bilderberg than the Japanese did back in the 1970s.[†]

****

[†] One obvious and persuasive candidate for arguing on China’s behalf is well-connected Sinophile and long-term Bilderberg participant, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Source link

[ad_2]

source https://earn8online.com/index.php/270317/the-seal-of-approval-bilderberg-and-the-origins-of-the-trilateral-commission-conspiracy-archive/

No comments:

Post a Comment